Deduce + Alloy: Tackling Trust Issues, One New Customer at a Time

Deduce’s partnership with Alloy restores trust and stops AI-driven synthetic identities

Deduce’s partnership with Alloy restores trust and stops AI-driven synthetic identities

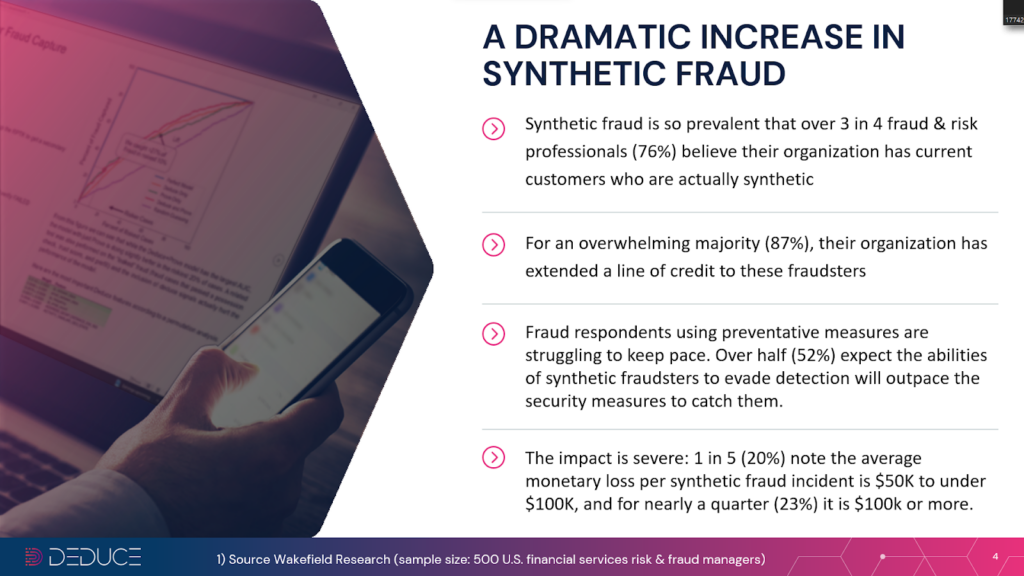

If you haven’t heard, synthetic fraud is making lots of noise in finserv circles. In fact, synthetic identities—a cross-stitching of stolen PII (Personally Identifiable Information) and made-up data—are officially the fastest-growing fraudsters in the US.

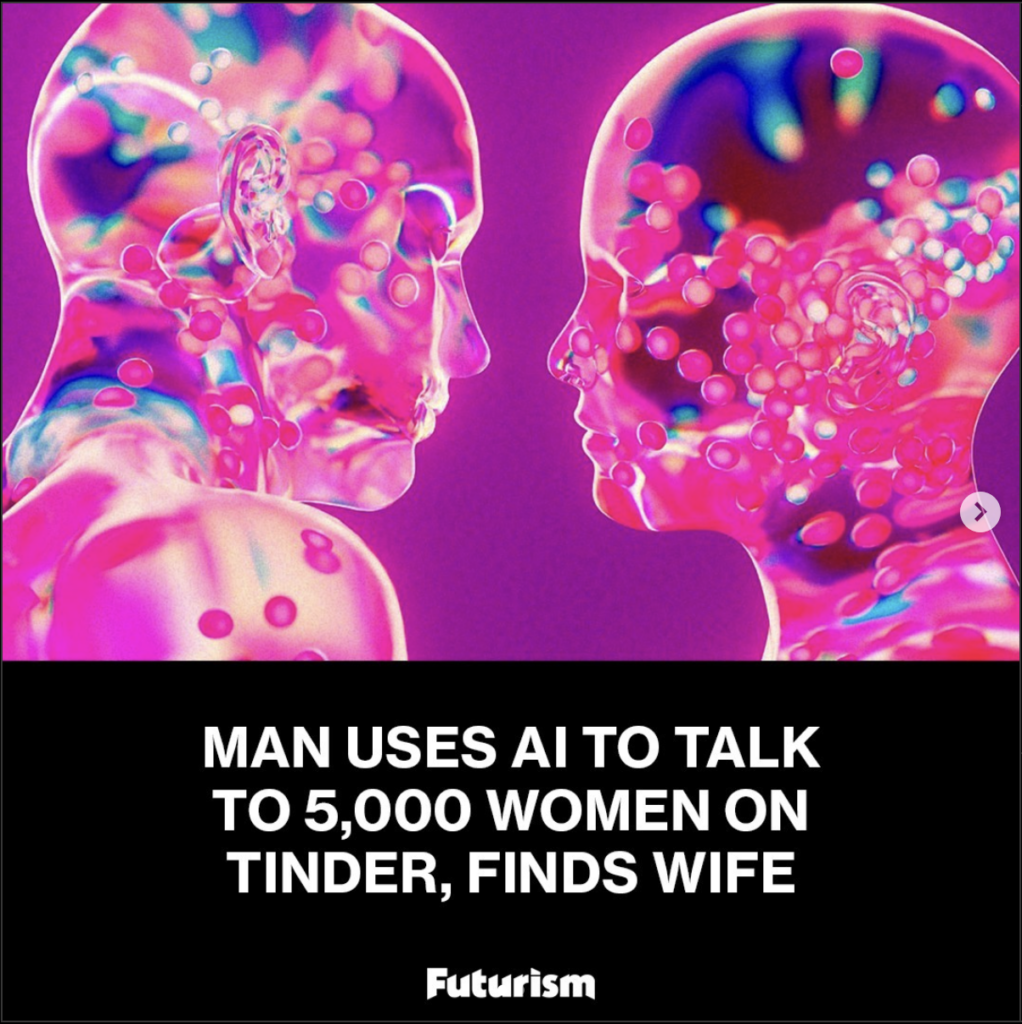

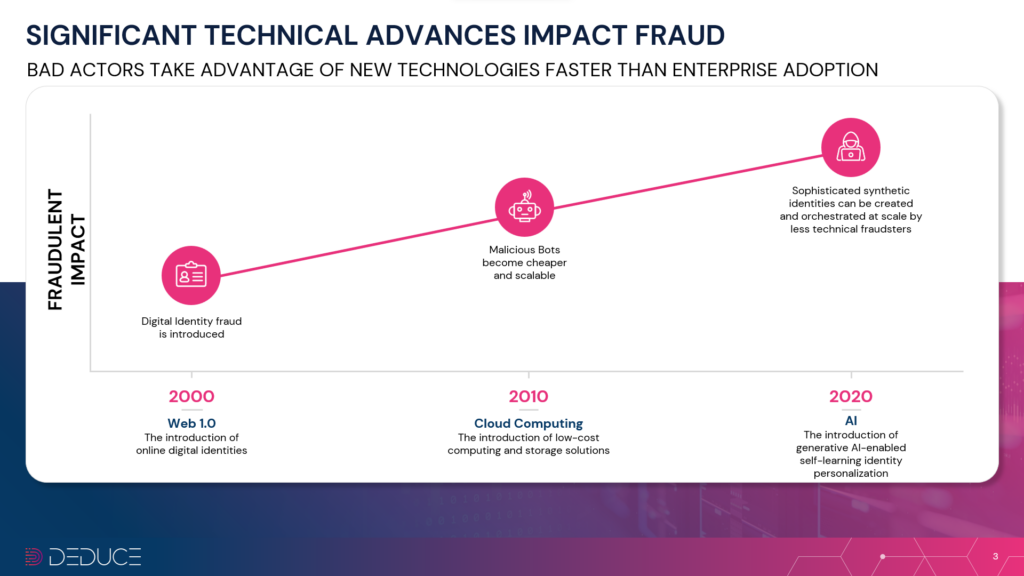

Of course, this is mostly due to those two inescapable letters: AI. Equipped with automated, human-like intelligence, fake identities are both innumerable and too realistic for most fintech companies to reliably stop.

This only increases the pressure on banks and fintechs who struggle to differentiate between real and fake customers. Trust is at an all-time low. And who can blame them? Accepting fake customers leads to major fraud losses and costly KYC (Know Your Customer) violations.

Recently, Deduce partnered with Alloy to help banks and finservs resolve these trust issues. Alloy’s customizable, end-to-end risk management solution serves almost 600 fintechs and financial institutions. Stack Deduce’s real-time, scalable identity intelligence on top, and identity data orchestration is a cinch.

Here’s a closer look at the ongoing struggle with customer verification, and how the Deduce-Alloy partnership leads to easier decisions, less risk, more compliance, and substantial savings.

Major trust issues

Stolen and synthetic identities have duped social media platforms, the gig economy, elections, and even universities. But banks, unquestionably, are their preferred target. Powered by Gen AI, synthetic identities are projected to cost banks a whopping $40B by 2027.

The Frankenstein-esque combo of real and fake PII already makes synthetic identities a tough catch. Gen AI is the coup de grâce. Aside from the added scalability, intelligence, and ease of deployment, Gen AI arms synthetic fraudsters with deepfake capabilities and the ability to create authentic-looking digital legends. Whether it’s a photo, video, or audio, synthetics can look or sound disturbingly lifelike—just ask the Hong Kong bank exec who was swindled out of $25.6M on a single call.

Decisioning is tougher than ever in today’s banking climate. Under immense pressure, financial institutions are lassoing as many new customers as possible with promises of lower APR rates and other attractive offers. Ostensibly, this may generate positive results, but manual review costs and other issues say otherwise.

One community bank we spoke to saw enrollment jump 25% quarter-over-quarter, but manual reviews jumped from 12% to 20% (anything over 7% is uh-oh territory). These same community banks are often used by fraudsters to bolster “thin file” credit reports. They’ll apply for a subprime loan and faithfully repay it with the intent of increasing their FICO score above 700, so they can take out a bigger loan elsewhere.

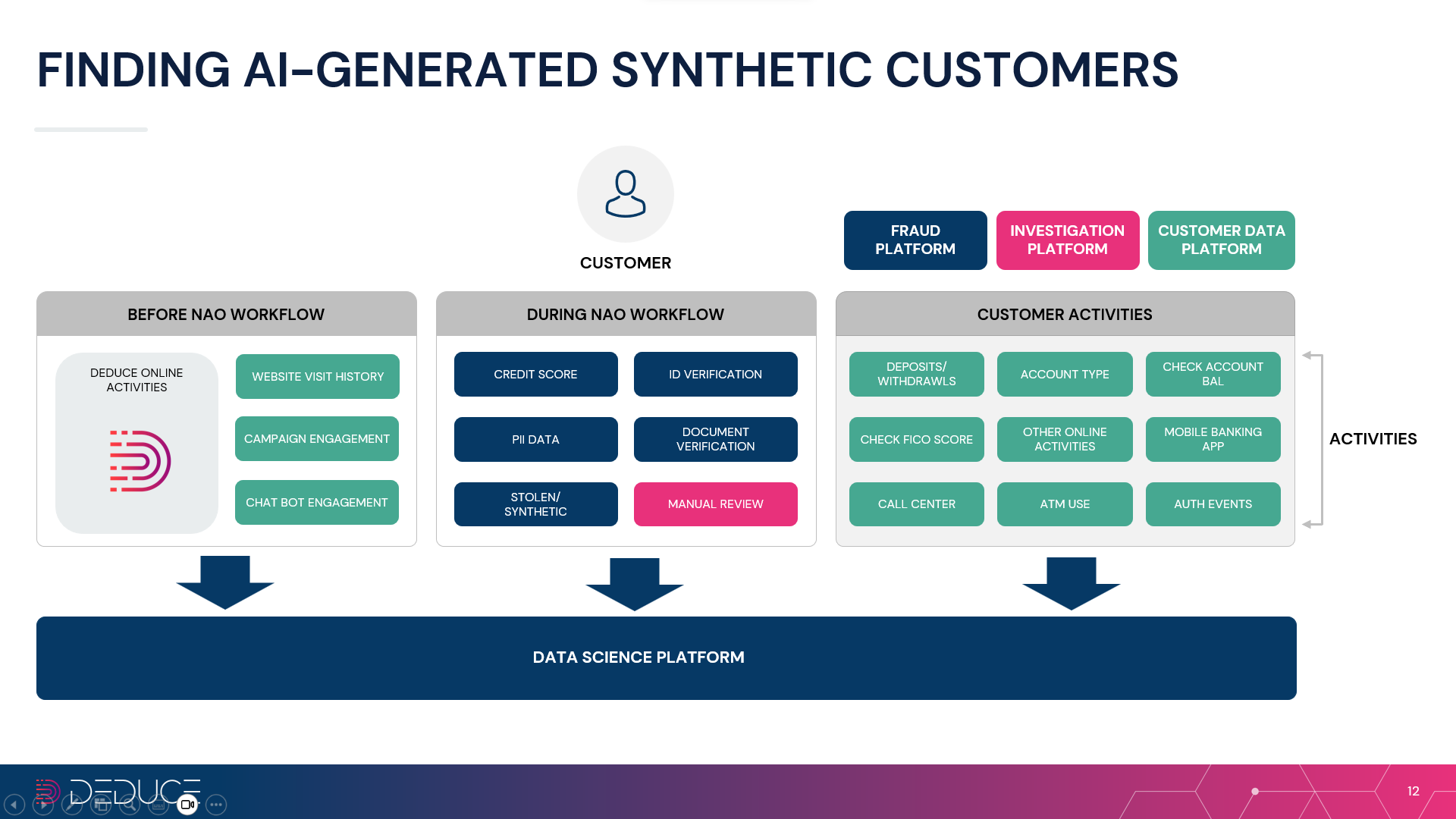

These AI-driven synthetic fraudsters will go above and beyond to appear like the real deal. Clicking on acquisition ads to start the account opening process, engaging with chatbots on banking websites—all to validate their interest when it comes time to apply. Synthetic identities can shapeshift into whichever customer a bank prefers. For example, consider a marketing campaign that’s targeting college students in need of a loan or credit card. Synthetics will embody these personas to appear more like students: .edu emails, social media posts about college, alumni connections on LinkedIn, etc.

Most banks and finservs simply don’t have the dynamic identity data to differentiate between good and fraudulent applicants at a high level.

How Alloy evens the odds

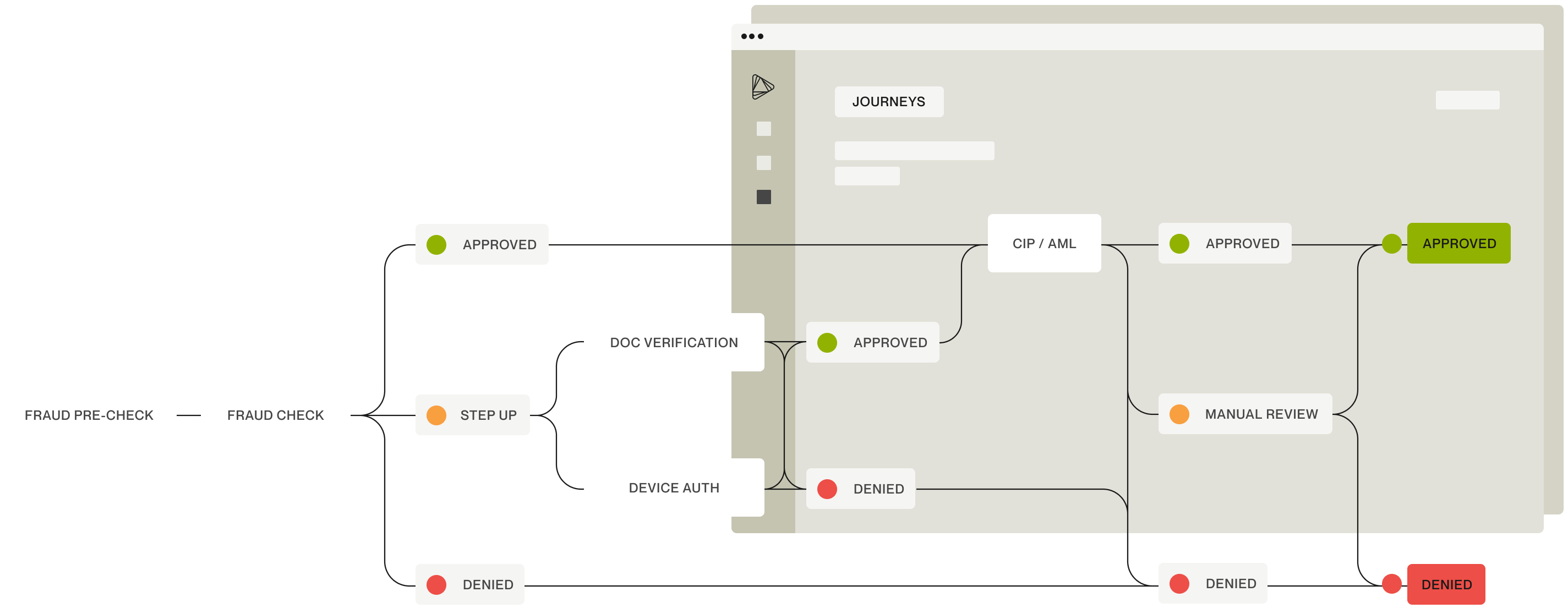

Alloy’s end-to-end identity risk solution enables banks and finservs to quickly and accurately make decisions about onboarding, credit underwriting, and potential AML (anti-money laundering) cases.

In short, Alloy is an orchestration platform. Like a master composer, it deftly arranges the various parts of the customer journey—including the onboarding workflow—into one UX-traordinary symphony.

In our new synthetic reality, Alloy’s automated, on-point decision making helps mitigate risk, facilitate compliance, and minimize identity verification costs. Alloy’s global network of data vendors simplifies identity risk for financial institutions, from step-up authentication (DocV) to manual reviews and OTP (one-time passcode) challenges.

And don’t forget passive identity affirmation—that’s where Deduce comes in.

Deduce + Alloy: the ultimate decisioning duo

trusted customers, and reduce the number of costly step-up tasks.

Deduce provides Alloy customers the real-time identity insights needed to spot trusted customers and sniff out synthetic fraudsters. In anticipation of the AI-driven fraud boom, Deduce built the largest activity-backed identity graph for fraud and risk in the US.

The Deduce Identity Graph, as we like to call it, conducts multicontextual, real-time data forensics at scale. Here’s how Deduce and its Identity Graph handles trust issues for banks and fintechs:

- Collects and analyzes real-time, activity-backed identity data from 1.5B+ daily authenticated events and 185M+ weekly users

- Employs entity embedding, deep learning neural networks, graph neural networks and generalized classification to recognize fraudulent activity patterns

- Matches activities between identities under review and other identities

- Spots new identity fraud threats as they emerge

Deduce also identifies traditional identity fraud while reducing false positives and secondary reviews: telltale signs of trust renewed.

Deduce’s partnership with Alloy is already paying dividends for banks (and their customers). One popular credit card rewards program relies on Deduce and Alloy to spot apps using stolen and synthetic identities without slowing down the user experience and triggering secondary reviews. In a competitive credit rewards landscape where seamless onboarding is the name of the game, reduced friction and verification costs are a must. Deduce and Alloy have it covered.

Identity verification you can bank on

Deduce knows your new customers very well. So well, in fact, that you can take it for a spin and see for yourself. Call it the “Deduce Passive Identity Affirmation Challenge.”

If you’re already an Alloy customer, it’s easy to see how effortlessly Deduce spots both trusted users and surefire fraudsters. Just follow these four easy steps:

1. Ask your Alloy representative about using Deduce.

2. Receive and enter your 30-day evaluation API key from Deduce.

3. Run your side-by-side, in-line evaluation against your current fraud prevention stack.

4. Compare the results. For each applicant Deduce trusts, what result did your existing solution provide? Did your solution’s result lead to increased friction, wasted step-up spend, or worse, application abandonment?

Not to spoil the fun, but at the end of your test drive expect Deduce to:

- Know more than 91% of your new applicants

- Label nearly 50% of new applicants as trusted, with 99.7% accuracy

Have any questions? Feel free to contact us. You can also find Deduce on the Alloy partner portal.